I want to build. Is this feasible?

- Brian

- Sep 26, 2020

- 7 min read

Detailing the steps required to determine if building on a given lot is feasible (Version: Western Washington 2020)

For this post to have context, a little rehash from our blog’s first post is necessary; my father (Dan) owns 2 lots at this location that consist of a total of 5 acres. We are currently living on the “main” lot on the east side of the property and will be purchasing the back (west) 1.87 acres where we will build our new home.

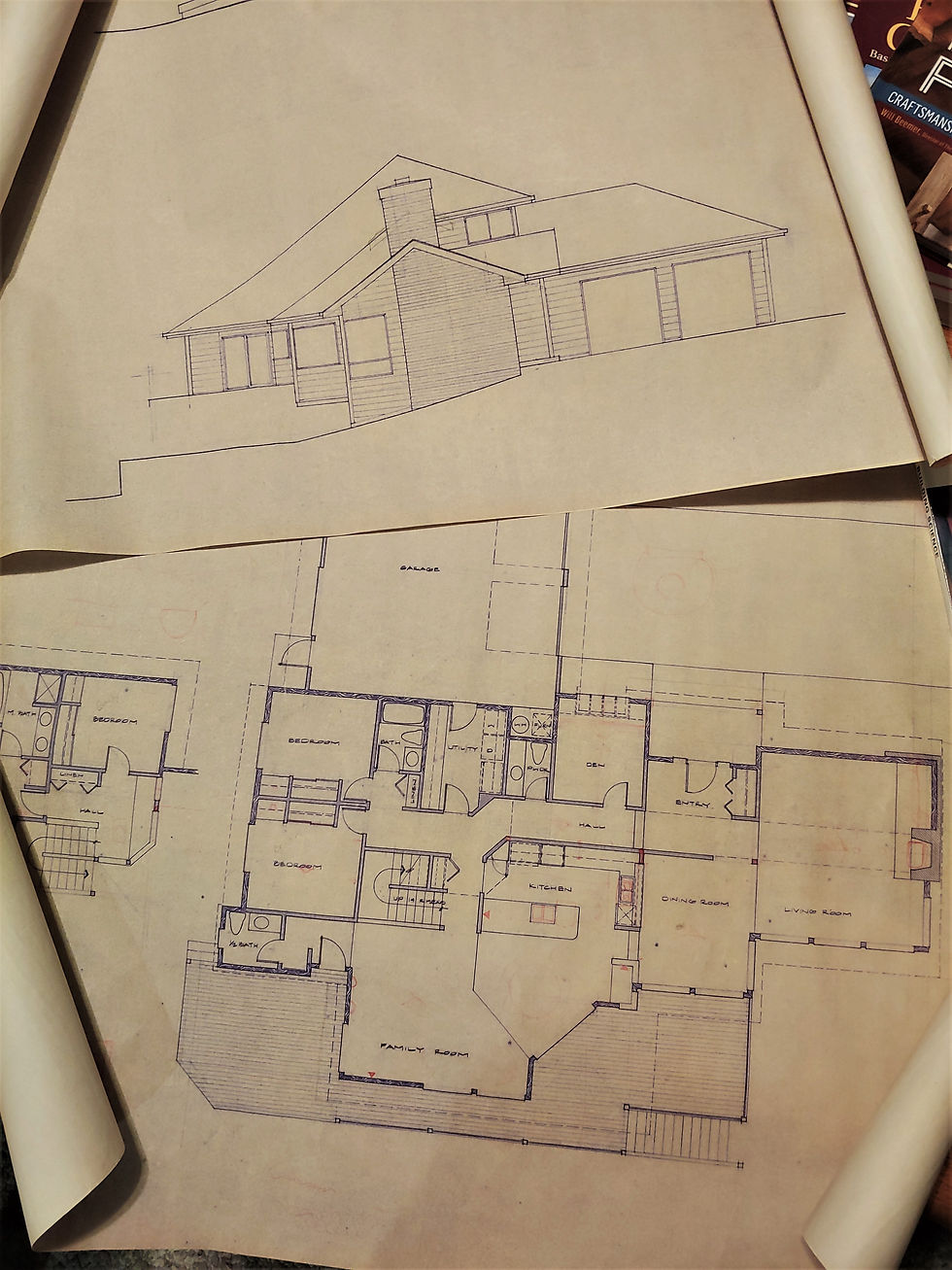

Anyways, back in the day (I am going to guess in 1992) my parents entertained the idea of building on the back/west portion of the property; they even went as far as having an initial floor plan and septic design drawn up. The septic system (Yes, we are waaaay too far out to be on sewer) was going to be “easy” because the lot is sloped. You see, on a sloped lot you can do a gravity feed system, which is about the simplest, cheapest, lowest maintenance system you can install (super lucky). Also, there was already an existing easement and driveway on the lot that was used to access my parents existing house (the house in which we are currently living), as well as providing access to the 2 neighboring residences to the west. The driveway started at the main road and headed directly west along the north boundary of both our east and west lot. Logistically it should be easy to build on the back lot; use the existing driveway to access it so there is no need for any new roads, easements, etc...W pretty much checked all the boxes: access (check), septic system feasibility (check), water rights (check; purchased a share way back in the day), necessary easements for utilities (check; power, water, cable, etc.). It is pretty much a layup.

Check out the old house plans that Dan still had! (Instead they opted for a remodel of current house on the main/east lot).

So fast forward (Let me do the math...) roughly 26 years and I decided developing this lot would be a fun project. I assumed it would be straightforward, given back in 1992 nobody put up a fuss when my parents were about to build. However, today things have changed...and there are a lot more hoops to jump through before you can just start digging in the ground. After some research I realized there was a fair amount of work that would be needed to determine if it were even feasible to build.

This blog post will focus on the initial work that went into preparing the lot and determine the feasibility of building upon it. Much of this work is also required when submitting permits; consequently, this will describe the early steps of the permitting process as well.

To keep this post short (relatively) I am going to list the required site-work items, in the order of which these items need to be completed prior to beginning the design of the house (Note: depending on the local laws, governing jurisdictions, and lot specifics, the logical order of operations could be different than it was for us):

1.) Site Survey

2.) Wetland Delineation

3.) Septic Percolation Test and Drainfield location identification

4.) Lot Topography

5.) Geotechnical Analysis and Critical Slopes (Note: this should be done but we skipped this as we already knew the soil and slopes were within spec to build)

Site Survey: We started by getting our lot surveyed by a local surveyor. An updated survey map showing the existing condition of the lot (boundary lines, easements, existing structures, etc.) is crucial for the entire process. It can be used later for many things including critical area maps, septic and drainfield map submittals, site plans, lot topos, etc. Additionally, as part of this process we planned to modify the boundary between our two lots, so the survey was required not only for our Building Permit submittal, but also for applying for a Boundary Line Adjustment (or a Short Plat Alteration... or wait, no it’s a Boundary Line adjustment.... No wait, it’s a Short Plat Alteration......Sorry about the aside here, this is foreshadowing a future post were I will explain how the county took months to decide which permit we actually needed to apply for. This held the project up for 9+ months, and ultimately, we needed to do our own research to know the county code well enough to tell them how to process it). Anyway, the lot survey is important, so do that first if you ever plan to build and the feasibility of the lot has not been confirmed. Often when buying a new lot, this work will already be complete.

Wetland Delineation: Our next step was to get our lot delineated for a wetland. This is important because a wetland, even if small, can have significant implications on where you can build, install a septic system/drainfield, put in utility trenches, driveways, etc. Additionally, it seems that about 1 out of 3 mud puddles will classify as a wetland (I joke here, but seriously it doesn’t take much), so in Western Washington, if you happen to be looking at a vacant lot, this is one of the first things that should be taken into consideration. I will say this should only be skipped if the lot happens to be at the very top of a mountain with steep downhill slopes in all directions so there is absolutely no chance of pooling water anywhere... In our case we knew that we likely had a wetland, given a “seasonal” pond/stream would form around springtime every year after a rainy winter. Our wetland was rated Class IV. Doesn't look like much, but here it is:

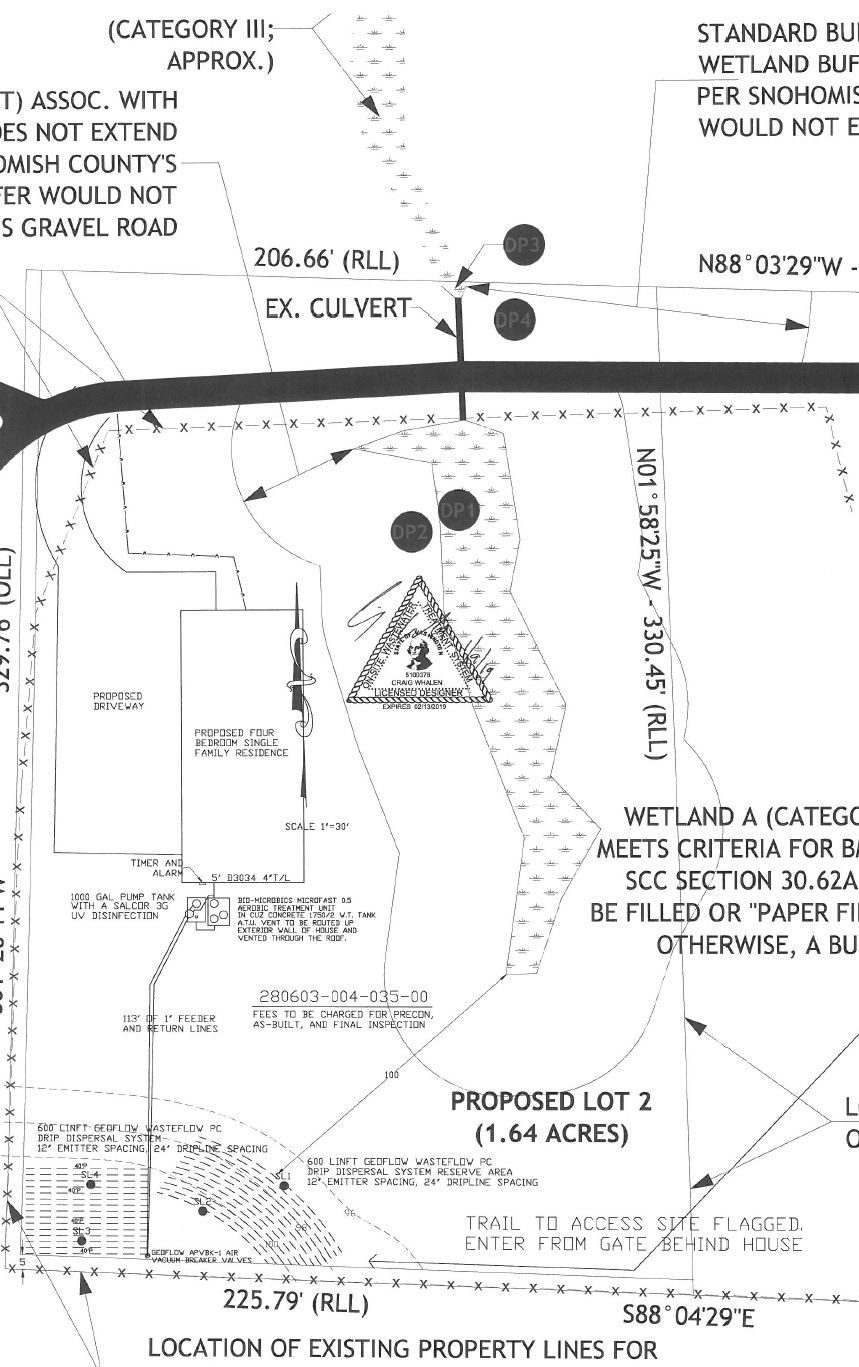

There are 4 ratings for wetlands (in this area anyway) I, II, III, and IV, where IV is the lowest. In our particular zoning, a class IV Wetland requires a 40 foot buffer (this buffer seems to vary depending on which county you are in and how your lot is zoned; ours is Rural 5-Acre). This means that no construction activity can take place within 40 feet of the wetland. If you decided you wanted to build within that buffer area, there are some mitigation processes that you can go through, but they require approvals, lots of time, and usually a significant cost. We got lucky and did not need to get into any of the mitigation mumbo jumbo, but the fact that we have a wetland required additional consideration throughout the process. Our Wetland Biologist was a fantastic, detailed, personable guy, from a company called Wetlands and Wildlife (a small local company since we tried to keep all our work as local as possible). He provided us with a wetland map that showed our boundary lines (taken from the lot survey!), wetland, and wetland buffer area.

Septic Percolation Test and Drainfield location identification: Our next step in determining feasibility was to get the soil percolation tested by a septic designer. We already perc tested our soil and knew it was good to go, and certainly if I were to buy a lot, I wouldn’t be opposed to perc testing myself, but unfortunately my perc test was not “official” so we brought in a septic designer to get this on the record. Remember the “gravity feed” septic system I talked about that my parents were going to install? Well, that septic system ultimately would have had a drainfield within the wetland buffer, so that is off the table. Nowadays it is code that drainfields must be placed outside the wetland buffer and they must be placed a minimum of 100 feet from a wetland (NOTE: THIS IS WHY YOU SHOULD DELINIATE THE WETLAND FIRST). On our lot (after our proposed boundary line adjustment) this allowed our drainfield only one location in the far southwest corner of the lot, which is uphill of just about everything. Now instead of a simple, inexpensive gravity feed system, we need a system that requires pumping from the septic tanks up hill (roughly 30 vertical feet) and over 100 feet away.

Oh well, at least the drainfield fits somewhere on the lot, or we would be back to wetland mitigation procedures, which would likely be more costly. Our designer moved forward with a septic design, submitted the design to the health department, and it was approved (a 3 month wait for this by the way). I ended up having to get on the horn with the health district to speed things along (something I hate having to do), apparently they didn’t have a GPS, map, smartphone, brain, etc. to help give them directions to the lot, or they couldn’t read, because a requirement for the application was to provide directions... the same directions I provided everyone involved in the entire process, all of which said “Nice directions, they made finding this place super easy,” or something to that extent.. Anyway... let us move on...

Geotechnical analysis and Critical Slopes: Our lot has no critical slopes (I believe in our area this is any slope over 33% grade) and we knew the soil was good, so for feasibility purposes, we skipped this. However, we did end up bringing in a Geotech to test our soils prior to pouring footings because of a request made by my structural engineer (even though we had to rotohammer our soil in places because it was as strong as concrete, no big deal).

Now that we determined the wetland buffer and where the septic and drainfield were going to go, we finally were able to determine where the house could sit. Lucky for us, it is right where we wanted it to be. Another note here: with the above site research/prep completed and the fact that we had water available (via a water share my parents purchased years ago) our lot feasibility was complete and we determined the lot to be buildable... Finally, I can move to something more interesting (designing the actual house)!

In other news, we (Brianna, Dan, and I) performed a lot topography (details in another post), and we did this ourselves with a transit (classic surveying tool that looks like a small telescope). It is the old school, but not sooo old school way of doing a lot topography. We decided paying a surveyor for this was unnecessary as it was not required by the County, however, it was necessary to determine our lot elevations to ensure a walk-out basement was possible. The remainder of the submittal process for both the building permit, wetland, septic system, and BLA/Short Plat Alteration will be continued in another post as well, so stay tuned...

Comments